Chapter 5: Nouns

The final part of the Ajrumiyyah (the longest one), deals with nouns. Here we will follow the same straightforward methodology of the book. As we have already learned, nouns can have three states: Raf’, Nasb and Khafdh. So first, we will learn all the grammatical situations where the noun can accept Raf’. Then we will learn all the cases of Nasb. Finally all the cases of Khafdh.

By the time we reach the end, inshaAllah, you will have clear picture of why each word has the haraka at the ending it does.

[toc]

بَابُ مَرْفُوعَاتِ الأَسْمَاءِ

The Nouns in the State of Raf’

اَلمَرْفُوعَاتُ سَبْعَةٌ، وَهِيَ: اَلْفَاعِلُ، وَاَلْمَفْعُولُ اَلَّذِي لَمْ يُسَمَّ فَاعِلُهُ، وَالمُبْتَدَأُ وَخَبَرُهُ، وَاسْمُ ( كَانَ ) وَأَخَوَاتِهَا، وَخَبَرُ ( إِنَّ ) وَأَخَوَاتِهَا، وَالتَّابِعُ لِلْمَرفُوعِ، وَهُوَ أَرْبَعَةُ أَشْيَاءَ: اَلنَّعْتُ، وَالْعَطْفُ، وَالتَّوْكِيدُ، وَالْبَدَلُ.

Translation:

The nouns which are marfū’ are seven:

- الفاعل (Verbal Subject -Doer)

- نائب فاعل (Object whose subject is not mentioned)

- المبتدأ (Nominal Subject)

- خبر المبتدأ (Predicate)

- اسم كان وأخواتها (Subject of Kana and its sisters)

- خبر إن وأخواتها (Predicate of Inna and its sisters)

- التابع للمرفوع (Followers of Marfu’ elements)

- النعت (Adjective)

- العطف (Conjuction)

- التوكيد (Corroboration)

- البدل (Substitution)

بَابُ الفَاعِلِ

The Verbal Subject

اَلْفَاعِلُ هُوَ: الاسْمُ اَلمَرْفُوعُ اَلمَذْكُورُ قَبْلَهُ فِعْلُهُ. وَهُوَ عَلَى قِسْمَيْنِ: ظَاهِرٍ، ومُضْمَرٍ.

Translation: A Verbal Subject is a Marfu’ noun before which the verb is mentioned, and it is of two types: explicit and implicit

The فاعل is the verbal subject or the subject in a verbal sentence – a sentence in Arabic that starts with a verb. The فاعل is always a noun and marfū’.

For instance, we can say:

قَامَ زَيدٌ – verbal sentence

We can also say:

زَيدٌ قَامَ – nominal sentence

If the verb is mentioned before the subject as in the first case, then it is فاعل. If the subject comes before as in the second sentence, then it is مبتدأ which we will look at later.

[thrive_leads id=’2260′]

The فاعل is divided into two types:

- الظاهر (explicit)

- المُضْمَر (implicit)

In the next part Ibn Ajrum mentions plenty of examples for each:

Explicit Nouns:

فَالظَّاهِرُ نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: قَامَ زَيْدٌ، وَيَقُومُ زَيْدٌ، وَقَامَ الزَّيدانِ، وَيَقُومُ الزَّيدانِ، وَقَامَ الزَّيدونَ، وَيَقُومُ الزَّيدون، وَقَامَ الرِّجَالُ، وَيَقُومُ الرِّجَالُ، وَقَامَتْ هِندُ، وَتَقُومُ هندُ، وقامَتِ الهِندانِ، وَتَقُومُ الهندان، وَقَامَتْ الهِنداتُ، وَتَقُومُ الهنداتُ، وَقَامَتْ الهُنُودُ، وَتَقُومُ الهُنُودُ، وَقَامَ أَخُوكَ، وَيَقُومُ أَخُوكَ، وَقَامَ غُلَامِي، وَيَقُومُ غُلَامِي، وَمَا أَشْبَهَ ذَلِكَ.

So the explicit nouns are like your saying,

“قَامَ زَيْدٌ، وَيَقُومُ زَيْدٌ، وَقَامَ الزَّيدانِ، وَيَقُومُ الزَّيدانِ، وَقَامَ الزَّيدونَ، وَيَقُومُ الزَّيدون، وَقَامَ الرِّجَالُ، وَيَقُومُ الرِّجَالُ، وَقَامَتْ هِندُ، وَتَقُومُ هندُ، وقامَتِ الهِندانِ، وَتَقُومُ الهندان، وَقَامَتْ الهِنداتُ، وَتَقُومُ الهنداتُ، وَقَامَتْ الهُنُودُ، وَتَقُومُ الهُنُودُ، وَقَامَ أَخُوكَ، وَيَقُومُ أَخُوكَ، وَقَامَ غُلَامِي، وَيَقُومُ غُلَامِي”

and whatever is similar to that.

All these are examples that ibn Ajrum mentions for apparent verbal subjects.

Implicit Nouns

As for مُضْمَر they are the subjects that are attached to the end of a verb:

والمُضمَر اِثْنَا عَشْرٌ، نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: ضَرَبْتُ، وَضَرَبْنَا، وَضَرَبْتَ، وَضَرَبْتِ، وَضَرَبْتُمَا، وَضَرَبْتُمْ، وَضَرَبْتُنَّ، وَضَرَبَ، وَضَرَبَتْ، وَضَرَبَا، وَضَرَبُوا، وَضَرَبْنَ.

And the implicit subjects are twelve, like your saying,

“ضَرَبْتُ، وَضَرَبْنَا، وَضَرَبْتَ، وَضَرَبْتِ، وَضَرَبْتُمَا، وَضَرَبْتُمْ، وَضَرَبْتُنَّ، وَضَرَبَ، وَضَرَبَتْ، وَضَرَبَا، وَضَرَبُوا، وَضَرَبْنَ”

If the فاعل is always in the state of raf’ then why do some of the words in the above examples of مُضْمَر end with other than dhamma?

Do you remember what we learned in the chapter of al-I’rab about Mabni and Majhul? If you look at the diagram, you will find that from the types of Mabni nouns is الضمائر. All of the above are Mabni nouns as they are ضمائر, so their i’rab is not shown through any indicator.

بَابُ المَفْعُولِ الَّذِي لَمْ يُسَمَّ فَاعِلُةٌ (نَائِبُ فَاعِلٍ)

The Object Whose Subject Is Not Mentioned

وَهُوَ: اَلاِسْمُ اَلمَرْفُوعُ اَلَّذِي لَمْ يُذْكَرْ مَعَهُ فَاعِلُهُ.

فَإِنْ كَانَ اَلْفِعْلُ مَاضِيًا ضُمَّ أَوَّلُهُ وَكُسِرَ مَا قَبْلَ آخِرِهِ، وَإِنْ كَانَ مُضَارِعًا ضُمَّ أَوَّلُهُ وَفُتِحَ مَا قَبْلَ آخِرِهِ.

Translation: And it is a noun which is in a state of Raf’ whose subject is not mentioned along with it. When the verb is in the past tense it’s first letter takes damma and the letter before the last takes kasrah. And if the verb is in the present tense, it’s first letter takes dhamma and the letter before the last takes fatha.

This is the same concept as passive voice in english. Say you want to say that an action has been done. But you don’t want to say who did it. That is when you use the نائب فاعل.

- The نائب فاعل takes the state of Raf’

- The verb before it gets dhamma on its first letter and kasra on the letter before the last, if it is in the past tense

- It gets dhamma on the first letter and sukun on the letter before the last if it is the present tense

For example:

You could say in active voice:

The boy ate the apple

أكَلَ الولدُ التفّاحَ

In passive voice or using نائب فاعل, you would say:

The apple was eaten.

أُكِلَ التُفّاحُ

An example from the Quran:

With فاعل:

وَلَقَدْ خَلَقْنَا الْإِنسَانَ مِن سُلَالَةٍ مِّن طِينٍ

With نائب فاعل:

وَخُلِقَ الْإِنْسَانُ ضَعِيفًا

More examples:

| نائب فاعل | فاعل |

|---|---|

| تُسَاقُ السّيَّارةُ سريعاً | يَسُوقُ زيدٌ السيّارةَ سريعاً |

| أجِيبَ السُّؤالُ (In the case of Alif, it changes to Ya) | أَجَابَ المعَلِّمُ السُّؤالَ |

| قُرِئَ القرآنُ | قَرَأَ القَارِئ القرآنَ |

| يُكْرَمُ الضيفُ | الكريمُ يُكْرِم ضيفَهُ |

| ضُرِبَ زَيدٌ | ضَرَبَ أحمدُ زيدًا |

The sentence with the نائب فاعل does not have a subject. It describes the action in passive voice without the subject being mentioned.

وَهُوَ عَلَى قِسْمَيْنِ: ظَاهِرٍ، ومُضْمَرٍ، فَالظَّاهِرُ نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: ( ضُرِبَ زَيْدٌ )، وَ( يُضْرَبُ زَيْدٌ )، وَ( أُكْرِمَ عَمْرٌو)، وَ( يُكْرَمُ عَمْرٌو). وَالمُضْمَرُ: اِثْنَا عَشَرَ، نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: ( ضُرِبْتُ، وَضُرِبْنَا، وَضُرِبْتَ، وَضُرِبْتِ، وَضُرِبْتُمَا، وَضُرِبْتُمْ، وَضُرِبْتُنَّ، وَضُرِبَ، وَضُرِبَتْ، وضُرِبَا، وَضُرِبُوا، وَضُرِبنَ ).

Translation: And it is of two types: explicit and implicit. As for the explicit, it is like your saying,

“وَيُضْرَبُ زَيْدٌ, وَأُكْرِمَ عَمْرٌو, وَيُكْرَمُ عَمْرٌو”

And the implicit are twelve types. Like your saying,

“ضُرِبْتُ, وَضُرِبْنَا, وَضُرِبْتَ, وَضُرِبْتِ, وَضُرِبْتُمَا, وَضُرِبْتُمْ, وَضُرِبْتُنَّ, وَضُرِبَ, وَضُرِبَتْ, وضُرِبَا, وَضُرِبُوا, وَضُرِبْنَ”

The نائب فاعل just like the فاعل can also be divided into الظاهر (explicit) and المُضْمَر (implicit). Mentioned in the text above are examples for both categories.

بَابُ اَلمُبْتَدَأِ وَالخَبَرِ

The Subject and its Predicate

اَلمُبْتَدَأُ هُوَ: اَلاِسْمُ اَلمَرْفُوعُ اَلْعَارِي عَنْ اَلْعَوَامِلِ اَللَّفْظِيَّةِ.

The Nominal Subject is a Noun in the state of Raf’ which is free from any grammatical agents (that affect it’s i’rab).

وَالخَبَرُ هُوَ: اَلاِسْمُ اَلمَرْفُوعُ اَلمُسْنَدُ إِلَيْهِ، نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: (زَيْدٌ قَائِمٌ) وَ (الزَّيْدَانِ قَائِمَانِ) و (الزَّيْدُونَ قَائِمُونَ).

And the Predicate is a Noun in the state of Raf’ which is linked to it (the subject), as in your saying,

“زَيْدٌ قَائِمٌ، والزيدانِ قَائِمَانِ، والزيدونَ قَائِمُونَ”

وَالمُبْتَدَأ قِسْمَانِ: ظَاهِرٌ ومُضْمَرٌ.

The Nominal Subject is two types: explicit and implicit.

فَالظَّاهِرُ : مَا تَقَدَّمَ ذِكْرُهُ.

As for the explicit, it is as mentioned before.

وَاَلمُضْمَرُ اثْنَا عَشَرَ، وَهِيَ: أَنَا، وَنَحْنُ، وَأَنْتَ، وَأَنْتِ، وَأَنْتُمَا، وَأَنْتُمْ، وَأَنْتُنَّ، وَهُوَ، وَهِيَ، وَهُمَا، وَهُمْ، وَهُنَّ، نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: أَنَا قَائِمٌ، وَنَحْنُ قَائِمُونَ، وَمَا أَشْبَهَ ذَلِكَ.

And the implicit is divided into twelve types:

أَنَا، وَنَحْنُ، وَأَنْتَ، وَأَنْتِ، وَأَنْتُمَا، وَأَنْتُمْ، وَأَنْتُنَّ، وَهُوَ، وَهِيَ، وَهُمَا، وَهُمْ، وَهُنَّ، نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: أَنَا قَائِمٌ، وَنَحْنُ قَائِمُونَ

And whatever resembles these.

وَالْخَبرُ قِسْمَانِ: مُفْرَدٌ، وَغَيْرُ مُفْرَدٍ.

And the Predicate is made up of two types: Singular and Compound.

فَالمُفْرَدُ نَحْوَ: زَيْدٌ قَائِمٌ.

The singular is like your saying,

زَيْدٌ قَائِمٌ (Zaid is standing)

وَغَيْرُ المُفْرَدِ، أَرْبَعَةُ أَشْيَاءٍ: الجَارُّ وَالمَجْرُورُ، وَالظَّرْفُ، وَالْفِعْلُ مَعَ فَاعِلِهِ، وَالمُبْتَدَأُ مَعَ خَبَرِهِ، نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: زَيْدٌ فِي الدَّاْرِ، وَزَيْدٌ عِنْدَكَ، وَزَيْدٌ قَامَ أَبُوهُ، وَزَيْدٌ جَارِيَتُهُ ذَاهِبَةٌ.

The Compound Predicate is divided into four types: 1) The Jaar and Majrur 2)The Circumstantial Preposition 3)The Verb and its Subject and 4) The Nominal Subject and its Predicate. Like your saying,

زَيْدٌ فِي الدَّاْرِ، وَزَيْدٌ عِنْدَكَ، وَزَيْدٌ قَامَ أَبُوهُ، وَزَيْدٌ جَارِيَتُهُ ذَاهِبَةٌ.

The Mubtada’ is pretty straightforward. It is the noun that comes at the beginning of the sentence, with nothing applied to it (like verbs, كان، إن etc.)

What is the difference between the فاعل and the مبتدأ?

The فاعل has a verb that comes before it or in other words, it is part of a verbal sentence. The مبتدأ is part of a nominal sentence.

The Khabar is the Predicate of the Mubtada’. It follows the pattern of the Mubtada’ – it is always in the state of Raf’ and it is single, dual or plural, depending on what form the Mubtada’ is in.

زيدٌ قَائِمٌ

الزَيدَانِ قَائِمَانِ

الزَيدُونَ قَائِمُونَ

Types of Mubtada’

Again the Mubtada’ is divided into الظاهر (explicit) and المُضْمَر (implicit).

الظاهر (explicit) is when it appears as in the examples above.

المُضْمَر (implicit) is when it appears as pronouns, for example:

أنا قائمٌ

نحن قائمون

هُوَ قَائِمٌ

Notice that الضمائرالمتصلة (attached pronouns) are not mentioned under the Mubtada’? Why is that?

Answer: The الضمائرالمتصلة always come after a verb, and therefore cannot be Mubtada’

Types of Predicate

The predicate occurs in two forms: singular and compound.

The singular predicate is when it occurs in the form of a single word or phrase: singular, dual or plural.

The compound predicate is when the predicate is made of a group of words. It can be of four types:

1.الجار والمجرور (A preposition and its object)

For example,

زَيدٌ فِي الدّارِ

Here the فِي الدّارِ forms the predicate.

2.الظرف (Adverbial expression)

Example:

زَيدٌ عِندَكَ

Why is this not a singular Khabar? Because عِندَكَ is not a single word. It is made of two things: the adverb: عند and the pronoun ك.

Another example:

زَيدٌ أَمامَ البَيتِ

3.الفعل مع خبره (A verb with its subject)

زَيدٌ قَامَ أَبُوهُ

Here the Khabar is formed by the verb and its subject together.

The same is true for the نائب فاعل.

زَيدٌ أُكِلَ طَعامُهُ

4.المبتدأ مع خبره (A subject with its predicate)

زَيدٌ بيتُهُ بَعيدٌ

محمدٌ خطُّهُ حَسَنٌ

In conclusion, both the Mubtada’ and it’s Khabar are always in the state of Raf’. And in case, the Khabar is a sentence or partial sentence as in the examples above, then it is also in the state of Raf’ as a whole. But in this case, the I’rab (of the Khabar part) is supposed and not shown. As for the individual elements of the Khabar formed by a sentence or compound sentence they are given the I’rab as in a normal sentence.

بَابُ اَلْعَوَاملِ اَلدَّاخِلَةِ عَلَى اَلمُبْتَدَأِ وَالخَبَرِ

Agents applied to the Subject and Predicate

وَهِيَ ثَلَاثَةُ أَشْيَاءَ: كَانَ وَأَخَوَاتُهَا، وَاِنَّ وَأَخَوَاتُهَا، وَظَنَنْتُ وَأَخَوَاتُهَا.

Translation: And They are divided into three categories: 1) Kana and its sisters 2) Inna and its sisters 3)Dhananthu and its sisters.

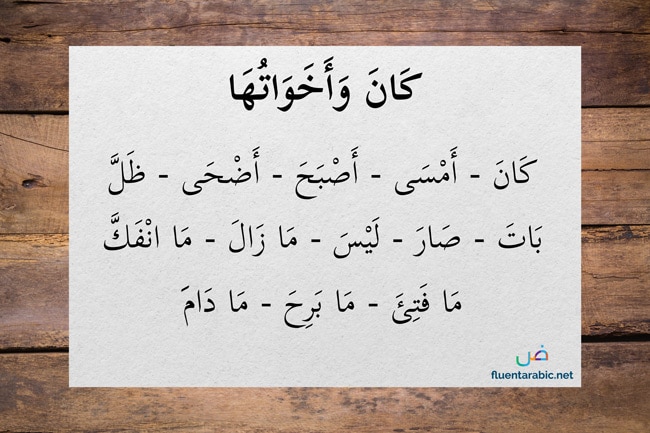

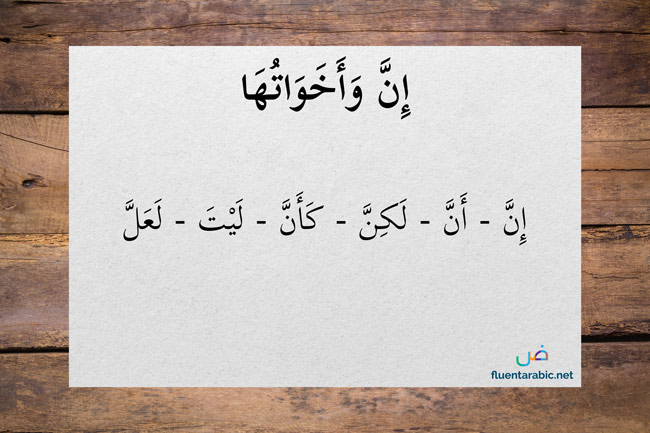

فَأَمَّا كَانَ وَأَخَوَاتُهَا، فَإِنَّهَا تَرْفَعُ اَلاِسْمَ، وَتَنْصِبُ اَلخَبَرَ، وَهِيَ: كَانَ، وَأَمْسَى، وَأَصْبَحَ، وَأَضْحَى، وَظَلَّ، وَبَاتَ، وَصَارَ، وَلَيْسَ، وَمَا زَالَ، وَمَا انْفَكَّ، وَمَا فَتِيءَ، وَمَا بَرِحَ، وَمَا دَامَ، وَمَا تَصَرَّفَ مِنْهَا نَحْوَ: كَانَ وَيَكُونُ وَكُنْ، وَأَصْبَحَ وَيُصْبِحُ وَأَصْبِحْ، تَقُولُ ( كَانَ زَيْدٌ قَائِمًا، وَلَيْسَ عَمْرٌو شاخصًا ) وَمَا أَشْبَهَ ذَلِكَ. وَأَمَّا إِنَّ وَأَخَوَاتُهَا، فَإِنَّهَا تَنْصِبُ الاسْمَ وَتَرْفَعُ الْخَبَرَ، وَهِيَ: إِنَّ، وَأَنَّ، وَلَكِنَّ، وَكَأَنَّ، وَلَيْتَ، وَلَعَلَّ، تَقُولُ: إِنَّ زَيْدًا قَائِمٌ، وَلَيْتَ عَمْرًا شَاخِصٌ، وَمَا أَشْبَهَ ذَلِكَ، وَمَعْنَى إِنَّ وَأَنَّ لِلتَّوْكِيدِ، وَلَكِنَّ لِلاِسْتِدْرَاكِ، وَكَأَنَّ لِلتَّشْبِيهِ، وَلَيْتَ لِلتَّمَنِّي، وَلَعَلَّ للتَّرَجِي والتَّوَقُعِ.

As for Kana and its sisters, they give Raf’ to the Nominal Subject and Nasb to the Predicate. Kana and her sisters are as follows:

كَانَ، وَأَمْسَى، وَأَصْبَحَ، وَأَضْحَى، وَظَلَّ، وَبَاتَ، وَصَارَ، وَلَيْسَ، وَمَا زَالَ، وَمَا انْفَكَّ، وَمَا فَتِيءَ، وَمَا بَرِحَ، وَمَا دَامَ

And that which can be extracted from these by way of verb conjugation like:

كَانَ وَيَكُونُ وَكُنْ، وَأَصْبَحَ وَيُصْبِحُ وَأَصْبِحْ

You can say for example,

كَانَ زَيْدٌ قَائِمًا، وَلَيْسَ عَمْرٌو شاخِصًَا

And whatever resembles this.

As for Inna and its sisters, they give Nasb to the Noun and Raf’ to the Predicate. Inna and its sisters are,

إِنَّ، وَأَنَّ، وَلَكِنَّ، وَكَأَنَّ، وَلَيْتَ، وَلَعَلَّ

You can say,

إِنَّ زَيْدًا قَائِمٌ، وَلَيْتَ عَمْرًا شَاخِصٌ

And whatever resembles this.

Both Inna and Anna are used for affirmation. Lakinna is used for rectification or correction. Ka’anna is used for comparison or to show likeness. Layta is used to express regret. La’alla is used to express anticipation and expectation.

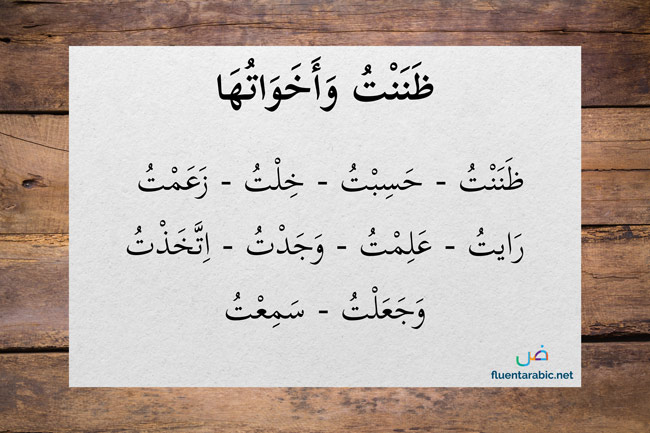

وَأَمَّا ظَنَنْتُ وَأَخَوَاتُهَا فَإِنَّهَا تَنْصِبُ المُبْتَدَأَ وَالْخَبَرَ عَلَى أَنَّهُمَا مَفْعُولَانِ لَهَا، وَهِيَ: ظَنَنْتُ، وَحَسِبْتُ، وَخِلْتُ، وَزَعَمْتُ، وَرَأَيْتُ، وَعَلِمْتُ، وَوَجَدْتُ، وَاِتَّخَذْتُ، وَجَعَلْتُ، وَسَمِعْتُ، تَقُولُ: ظَنَنْتُ زَيْدًا مُنْطَلِقًا، وَخِلْتُ عَمْرًا شاخِصًا، وَمَا أَشْبَهَ ذَلِكَ.

As for Dhananthu and its sisters, they give Nasb to both the Subject and Predicate, as they are treated as its Objects. They are:

ظَنَنْتُ، وَحَسِبْتُ، وَخِلْتُ، وَزَعَمْتُ، وَرَأيتُ، وَعَلِمْتُ، وَوَجَدْتُ، وَاِتَّخَذْتُ، وَجَعَلْتُ، وَسَمِعْتُ

You can say,

ظَنَنْتُ زَيْدًا مُنْطَلِقًا، وَخِلْتُ عَمْرًا شاخِصًَا

And whatever resembles this.

The Nawasikh

This is a very easy chapter. The Nawasikh are agents that are added to the Mubtada’ to express different meanings.

There are three groups of these agents:

Kana is used to express a meaning similar to ‘was’ is English. Inna is used for emphasis and Dhananthu means ‘I thought’. We won’t delve into the meanings of the ‘sisters’ or the other words that are grouped with each of them for now, but just remember they follow the same rules as the leader of the group, although each has its own meaning.

Rules of the Nawasikh

As for Kana and its sisters, they cause the Mubtada’ to take Raf’ and Khabar to take Nasb.

As for Inna and its sisters, they do the exact opposite of Kana, they cause the Mubtada’ to take Nasb and Khabar to take Raf’

And finally, Dhananthu causes both Mubtada’ and Khabar to take Nasb. This is because both the Mubtada’ and Khabar act as objects in the case of these agents.

| الخبر | المبتدأ | الناسخ |

|---|---|---|

| النصب | النصب | ظَنَنْتُ |

| الرفع | النصب | إن |

| النصب | الرفع | كان |

Examples:

وَكَانَ اللَّهُ شَاكِرًا عَلِيمًا

إِنَّ اللَّهَ غَفُورٌ رَّحِيمٌ

ظَنَنْتُ زَيدًا منطَلِقًا

Question: What if the Khabar of one of these agents is compound instead of singular?

Answer: The whole compound sentence or half-sentence takes the state given to it by the agent. For example,

كان محمدٌ يحبُّ قرآءَةَ الكُتُبِ

Here محمدٌ is the Mubtada’ and it takes the state of Raf’. The indicator is dhamma which is ‘apparent’.

The Khabar is made up of the entire sentence: يحبُّ قرآءَةَ الكُتُبِ

Here the يحبُّ is Marfu’ because it is a present tense verb.

قرآءَةَ is Mansub because it is the object or Maf’ul bihi (مفعول به).

الكُتُبِ is Majrur because it is mudhaf ilaihi (مضاف إليه)

As for the whole Khabar it takes the ruling of nasb which is supposed and not apparent as it is the khabar of kana.

More examples:

كَانَ المُسَجِّلُ سَليماً

ما زالَ المَطَرُ نازِلًا

وَلَا يَزَالُونَ مُختَلِفِينَ

The Khabar coming before the Mubtada’:

If the Khabar is an adverb (ظرف) or جار ومجرور the Khabar of both Kana and Inna can come before the subject. For example:

إنَّ في ذَلك لعِبْرَةً

وكَانَ حَقَّا عَلَيْنَا نَصْرُ المُؤمِنِينَ

If you are confused between the Mubtada’ and the Khabar, just remember: The Mubtada is what you are describing – ‘the subject’ and the Khabar is what you are saying about it – ‘the predicate’. So it is easy to tell them apart once you know the meaning of the sentence.

The Mubtada’ is the thing you are talking about, and the Khabar is what you are saying about it.

Examples for Dhanantu and its sisters:

حَسِبْتُ عَمْرًا صاَدِقًا

ظَنَنْتُ التِّلْمِيذَ فَاهِمًا

زَعَمْتُ زَيْدًا مُحَمَّدًا (أي ظَننتُهُ مُحَمَّدًا)

لَوَجَدُوا اللَّهَ تَوَّابًا رَّحِيمًا

بَابُ اَلنَّعْتِ

Adjectives

اَلنَّعْتُ تَابِعٌ لِلْمَنْعُوتِ فِي رَفْعِهِ، وَنَصْبِهِ، وَخَفْضِهِ، وَتَعْرِيفِهِ، وَتَنْكِيرِهِ، تَقُولُ قَامَ زَيْدٌ اَلْعَاقِلُ، وَرَأَيْتُ زَيْدًا اَلْعَاقِلَ، وَمَرَرْتُ بِزَيْدٍ اَلْعَاقِلِ.

Translation: The adjective follows the object of description in its Raf’, Nasb and Khafdh states, and also in its definiteness and indefiniteness. You can say, for example,

قَامَ زَيْدٌ العَاقِلُ، وَرَأَى زَيْدًا العَاقِلَ، وَمَرَرْتُ بِزَيْدٍ العَاقِلِ

وَالمَعْرِفَةُ خَمْسَةُ أَشْيَاءَ: اَلاِسْمُ اَلمُضْمَرُ نَحْوُ أَنَا وَأَنْتَ، وَالاِسْمُ اَلْعَلَمُ نَحْوُ: زَيْدٌ وَمَكَّةُ، وَالاِسْمُ اَلمُبْهَمُ نَحْوُ: هَذَا، وَهَذِهِ، وَهَؤُلَاءِ، وَالاِسْمُ اَلَّذِي فِيهِ اَلْأَلِفُ وَاللاَّمُ نَحْوُ اَلرَّجُلُ وَالغُلَامُ، وَمَا أُضِيفَ إِلَى وَاحِدٍ مِنْ هَذِهِ اَلْأَرْبَعَةِ.

The Definite Nouns are five types:

1)Implicit Nouns like: أَنَا, وَأَنْتَ

2)Proper Nouns like: زَيْدٌ وَمَكَّةُ

3)Ambiguous Nouns like: هَذَا وَهَذِهِ وَهَؤُلَاءِ

4)Nouns with Alif-Lam like: الرَّجُلُ وَالغُلَامُ

5)Nouns which are compounded with one of the above four.

وَالنَّكِرَةُ، كُلُّ اِسْمٍ شَائِعٍ فِي جِنْسِهِ لَا يَخْتَصُّ بِهِ وَاحِدٌ دُونَ آخَرَ، وَتَقْرِيبُهُ كُلُّ مَا صَلَحَ دُخُولُ اَلْأَلِفِ وَاللَّامِ عَلَيْهِ، نَحْوُ: اَلرَّجُلُ، والفرَسُ.

And the indefinite noun consists of every noun in its general class and is not restricted to one group. It may be approximated that the indefinite includes all the words that agree to the addition of alif-lam to them, like: الرَّجُلُ وَالفَرَسُ

The final part of the مرفوعات or the nouns in Raf’ are the توابع. These are elements that follow the grammatical state and form of the word before it. The first of these is the نعت.

The نعت or the صفة is the adjective used to show attributes of the noun. It takes the same form of the noun that it describes. For example:

قام زيدٌ العاقلُ

ورأيتُ زيداً العاقلَ

ومررتُ بزيدٍ العاقلِ

There are two things that العاقل follows from the noun زيد in these sentences:

- The grammatical state: Raf’, Nasb and Khafdh.

- The definite or indefinite state of the noun: زيذ is a definite noun as it represents a specific person. If it was an indefinite noun like رَجُل, the Na’at will also be indefinite:

مَرَرْتُ بِرَجُلٍ عَاقِلٍ

The nouns which are Ma’rifa (Definite) which cause the adjoining adverb (نعت or صفة) to be Ma’rifa can be classified into five categories:

| Example | Element |

|---|---|

| قلمُ زيدٍ | ما أُضيف إلى هذه الأربعة (What is attached to any of these four) |

| الرجل، الغُلام | الاسم الذي فيه الألف واللام(Nouns containing alif-lam) |

| هذا، هذه، هؤلاء | الاسم المبهم أو الموصول (Demonstrative Pronouns) |

| مكة، زيد، محمد | الاسم العلم (Proper Nouns) |

| أنا، أنت | الاسم المضمر (Personal Pronouns) |

Everything outside this is indefinite.

Tip: An easy way to tell if a noun is definite or indefinite is to see it can accept the alif lam. If it can, then when used without the alif lam, it is indefinite. If it cannot accept the alif lam, then it is definite in its stand-alone form. We can say الرجل, so رجل is indefinite. We don’t say المحمد. So محمد is definite.

بَابُ العَطفِ

Conjunctions

وَحُرُوفُ اَلْعَطْفِ عَشَرَةٌ، وَهِيَ: الوَاوُ، وَالْفَاءُ، وَثُمَّ، وَأَوْ، وَأَمْ، وَإِمَّا، وَبَلْ، وَلَا، وَلَكِنْ، وَحَتَّى فِي بَعْضِ المَوَاضِعِ.

Translation: The Particles of Conjunction are ten: Waw, Fa, Thumma, Aww, Amm, Imma, Bal, La, Lakin, and in some cases Hatta.

فَإِنْ عَطَفْتَ بِهَا عَلَى مَرْفُوعٍ رَفَعْتَ، أَوْ عَلَى مَنْصُوبٍ نَصَبْتَ، أَوْ عَلَى مَخْفُوضٍ خَفَضْتَ، أَوْ عَلَى مَجْزُومٍ جَزَمْتَ، تَقُولُ ( قَامَ زَيْدٌ وَعَمْرٌو، ورَأَيْتُ زَيْدًا وَعَمْرًا، وَمَرَرْتُ بِزَيْدٍ وَعَمْرٍو، وَزَيْدٌ لَمْ يَقُمْ وَلَمْ يَقْعُدْ ).

So if a word is conjoined with a Marfu’ word, it takes Raf’, if it conjoined with a Mansub word, it takes Nasb, and if it is conjoined with a Makhfudh word it takes Khafdh, and if it is conjoined with a Majzum word it takes Jazm. For example,

قَامَ زَيْدٌ وَعَمْرٌو، وَرَأى زَيْدًا وَعَمْرًا، وَمَرَرْتُ بِزَيْدٍ وَعَمْرٍو، وَزَيْدٌ لَمْ يَقُمْ وَلَمْ يَقْعُدْ.

A simple way to explain the ‘Atf is that they are the elements used to connect words together. Similar to ‘and’ and ‘or ‘ in English. However, there are a few additional words that come under this category in Arabic as mentioned in the text above.

When you say,

قام زيدٌ وعَمرٌو

The و is used to add عمرو along with زيد

عمرو here follows the grammatical state of زيد

More examples:

إِنَّ الصَّفَا وَالْمَرْوَةَ مِن شَعَائِرِ اللَّهِ

An important ruling derived from the Quran using this rule:

يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا إِذَا قُمْتُمْ إِلَى الصَّلاةِ فَاغْسِلُوا وُجُوهَكُمْ وَأَيْدِيَكُمْ إِلَى الْمَرَافِقِ وَامْسَحُوا بِرُؤُوسِكُمْ وَأَرْجُلَكُمْ إِلَى الْكَعْبَيْنِ (المائدة:6)

In the ayah above, Allah ﷻ tells us how to make Wudu (ablution).

Here the verb اغْسِلُوا (wash) is followed by the object وُجُوهَكُمْ.

And then أَيْدِيَكُمْ (hands) is connected to the previous object by و. It follows the state of the previous noun as it is ‘Atf.

Then comes the verb امْسَحُوا (wipe) بِرُؤُوسِكُمْ (your head. It is in Jarr, because of the harf ب at the beginning making it جار and مجرور).

Now the و is used again to add another part: أَرْجُلَكُمْ. But here it is not in Jarr like the noun before it, but it is in Nasb.

What does this mean?

It means that أَرْجُلَكُمْ is not connected to بِرُؤُوسِكُمْ but to the noun before that which is also in the state of Nasb: وُجُوهَكُمْ.

Let’s look at the Sahih international translation for this ayah:

“O you who have believed, when you rise to [perform] prayer, wash your faces and your forearms to the elbows and wipe over your heads and wash your feet to the ankles…”

How do we know it is ‘wash your feet’ and not ‘wipe your feet’? Because it is أَرْجُلَكُمْ and not أَرْجُلِكُمْ

Some more examples:

جاءَ زيدٌ ثُمَ عَمرٌو

جاءَ زيدٌ بَلْ عَمرٌو

قامَ زيدٌ لا عَمرٌو

ما جاء محمدٌ لكنْ عبدُ اللهِ ( إنّ which is a sister of لكنّ Note it is not )

حتى only in some cases because it can also be used as a harf jarr for example:

أكلتُ السَّمَكَةَ حتى رأسَها

حتى مَطْلَعِ الفجْرِ

بَابُ التَّوكِيدِ

Corroboration

اَلتَّوْكِيدُ تَابِعٌ لِلْمُؤَكَّدِ فِي رَفْعِهِ وَنَصْبِهِ وَخَفْضِهِ وَتَعْرِيفِهِ.

وَيَكُونُ بِأَلْفَاظٍ مَعْلُومَةٍ، وَهِيَ: اَلنَّفْسُ، وَالْعَيْنُ، وَكُلُّ، وَأَجْمَعُ، وَتَوَابِعُ أَجْمَعَ، وَهِيَ أَكْتَعُ، وَأَبْتَعُ، وَأَبْصَعُ، تَقُولُ: قَامَ زَيْدٌ نَفْسُهُ، وَرَأَيْتُ القَوْمَ كُلَّهُمْ، وَمَرَرْتُ بِالْقَوْمِ أَجْمَعِينَ.

The Article of Corroboration follows its object in its Raf’, Nasb and Khafdh, as well as in its definiteness and indefiniteness.

Corroboration is established with the following words:

النَّفْسُ، وَالعَيْنُ، وَكُلُّ، وَأَجْمَعُ

And words extracted from أجمع like:

أكْتَعُ، وَأَبْتَعُ، وأَبْصَعُ

Examples of this are:

قَامَ زَيْدٌ نَفْسُهُ، وَرَأَى القَوْمَ كُلَّهُمْ، وَمَرَّرْتُ بِالقَوْمِ أَجْمَعِينَ.

The particles of corroboration or توكيد are used to confirm and emphasise.

For example:

قام زيدٌ نفسُهُ

Zaid stood up, he himself!

أنتَ الطالبُ نفسُهُ

You are the student? The same one?

جاءَتْ العائلةُ كُلُّهُم

The family came, all of them.

The corroborative particle follows the grammatical state of the word before it.

More examples:

لَأَمْلَأَنَّ جَهَنَّمَ مِنَ الْجِنَّةِ وَالنَّاسِ أَجْمَعِينَ

فَسَجَدَ الْمَلَائِكَةُ كُلُّهُمْ أَجْمَعُونَ

بَابُ البَدَلِ

Substitution

إِذَا أُبدِلَ اِسْمٌ مِنْ اِسْمٍ، أَوْ فِعْلٌ مِنْ فِعْلٍ تَبِعَهُ فِي جَمِيعِ إِعْرَابِهِ.

وَهُوَ عَلَى أَرْبَعَةِ أَقْسَامٍ: بَدَلُ اَلشَّيْءِ مِنْ اَلشَّيْءِ، وَبَدَلُ اَلْبَعْضِ مِنْ اَلْكُلِّ، وَبَدَلُ اَلاِشْتِمَالِ، وَبَدَلُ اَلْغَلَطِ، نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ ( قَامَ زَيْدٌ أَخُوكَ، وَأَكَلْتُ اَلرَّغِيفَ ثُلُثَهُ، وَنَفَعَنِي زَيْدٌ عِلْمُهُ، وَرَأَيْتُ زَيْدًا اَلْفَرَسَ)، أَرَدْتَ أَنْ تَقُولَ: اَلْفَرَسَ فَغَلِطْتَ فَأَبْدَلْتَ زَيْدًا مِنْهُ.

If a noun is substituted for another noun, or a verb is substituted for another verb, it follows the original in all its I’rab (Grammatical States)

And it (Substitution) is four types: 1)Complete Substitution 2)The Substitution of a part from the whole 3)Substitution of content 4)Substitution based on error.

Some examples are,

قَامَ زَيْدٌ أَخُوكَ, وَأَكَلْتُ الرَّغِيفَ ثُلُثَهُ, وَنَفَعَنِي زَيْدٌ عِلْمُهُ

رَأَى زَيْدًا الفَرَسَ

In the above sentence you wanted to say رأيتُ الفَرَسَ، but by mistake, you said زَيْدًا, after which you substituted it for the correct word ( الفَرَسَ).

The Badal can be a noun that substitutes another noun or a verb that substitutes another verb.

What is implied by substitution here?

If you say:

أَكَلتُ التُفّاحَ

I ate the apple

And then use another word after it which substitutes or replaces the meaning or a part of the meaning of the word used before that is the Badal.

An example of that is:

أَكَلتُ التُفّاحَ نِصفَهُ

I ate the apple, half of it.

Notice how the badal ( نِصفَهُ), changes or substitutes the original meaning?

In the case of the example, the badal does not substitute the entire word but changes the meaning partially to ‘half of it’ (from the entire apple)

The Badal is of four types:

| Example | Type |

|---|---|

| رأيت زيدا….الفرسَ (In correction of a mistake) | بدل الغلط (Substitution for a mistake) |

| أعجبَني زيدٌ عِلْمُه | بدلُ الاشتمال (Substitution of Content) |

| حفِظتُ القرانَ ثُلُثَهُ | بدلُ البعضِ من الكلّ (Partial Substitution) |

| جاء زيدٌ أخوكَ | بدلُ الشيء من الشيء (Complete Substitution) |

Example for Badal of verbs:

وَمَن يَفْعَلْ ذَٰلِكَ يَلْقَ أَثَامًا * يُضَاعَفْ لَهُ الْعَذَابُ يَوْمَ الْقِيَامَةِ وَيَخْلُدْ فِيهِ مُهَانًا

In the above example from the Quran, يُضَاعَفْ is badal for يَلْقَ. Both are Majzum in this case. يَلْقَ by the removal of alif.

بَابُ مَنْصُوبَاتِ اَلأَسْمَاءِ

The Nouns in the State on Nasb

اَلمَنْصُوبَاتُ خَمْسَةَ عَشَرَ، وَهِيَ: اَلمَفْعُولُ بِهِ، وَالمَصْدَرُ، وَظَرْفُ اَلزَّمَانِ، وَظَرْفُ اَلمَكَانِ، وَالحَالُ، وَالتَّمْيِيزُ، وَالمُسْتَثْنَى، وَاسْمُ لَا، وَالمُنَادَىُ، وَالمَفْعُولُ مِنْ أَجْلِهِ، وَالمَفْعُولُ مَعَهُ، وَخَبَرُ كَانَ وَأَخَوَاتِهَا، وَاِسْمُ إِنَّ وَأَخَوَاتِهَا، وَالتَّابِعُ لِلْمَنْصُوبِ، وَهُوَ أَرْبَعَةُ أَشْيَاءَ: النَّعْتُ، وَالْعَطْفُ، وَالتَّوْكِيدُ، وَالْبَدْلُ.

Translation: The Nouns in the state of Nasb are fifteen: the direct object, the verbal noun (infinitive), the adverbial of time, the adverbial of space, the circumstantial qualifier, the specifying element, the exception, the noun of Laa (لا), the vocative, the causative object, the accompanying object, the predicate of Kana (كان)and its sisters, the Noun of Inna (إن) and its sisters, and the nouns that follow any of the mentioned Mansubs; they are four types: adjective, conjunction, corroboration, and the substitution.

The Mansubat, give us more information about the verb of the sentence. For example, the object tell us what the action is being done to. The ظَرْفُ الزمان tells us when the action is being done. And so on.

بَابُ اَلمَفْعُولِ بِهِ

The Object

وَهُوَ: اَلاِسْمُ اَلمَنْصُوبُ اَلَّذِي يَقَعُ بِهِ اَلْفِعْلُ، نَحْوَ ضَرْبَتُ زَيْدًا، وَرَكِبْتُ الفَرَسَ.

It’s the Mansub noun to which the verb’s action occurs. Like: I hit Zayed, I rode the horse.

وَهُوَ قِسْمَانِ: ظَاهِرٌ، ومُضْمَرٌ.

And it’s two types: explicit and Implicit (hidden).

فَالظَّاهِرُ: مَا تَقَدَّمَ ذِكْرُهُ.

The explicit: it has already been mentioned above.

وَالمُضْمَرُ قِسْمَانِ: مُتَّصِلٌ، وَمُنْفَصِلٌ.

The implicit object consists of two types: connected and separate.

فَالمُتَّصِلُ اِثْنَا عَشَرَ، وَهِيَ: ضَرَبَنِي، وَضَرَبَنَا، وَضَرَبَكَ، وَضَرَبَكِ، وَضَرَبَكُمَا، وَضَرَبَكُمْ، وَضَرَبَكُنَّ، وَضَرَبَهُ، وَضَرَبَهَا، وَضَرَبَهُمَا، وَضَرَبَهُمْ، وَضَرَبَهُنَّ.

The connected object is twelve types: (ضَرَبَنِي), (ضَرَبَنَا), (ضَرَبَكَ), (ضَرَبَكِ), (ضَرَبَكُمَا), (ضَرَبَكُمْ), (ضَرَبَكُنَّ), (ضَرَبَهُ), (ضَرَبَهَا), (ضَرَبَهُمَا), (ضَرَبَهُمْ), and (ضَرَبَهُنَّ).

وَالمُنْفَصِلُ اِثْنَا عَشَرَ، وَهِيَ: إِيَّايَ، وَإِيَّانَا، وَإِيَّاكَ، وَإِيَّاكِ، وَإِيَّاكُمَا، وَإِيَّاكُمْ، وَإِيَّاكُنَّ، وَإِيَّاهُ، وَإِيَّاهَا، وَإِيَّاهُمَا، وَإِيَّاهُمْ، وَإِيَّاهُنَّ.

The separate object is twelve types: (إِيَّايَ), (إِيَّانَا), (إِيَّاكَ), (إِيَّاكِ), (إِيَّاكُمَا), (إِيَّاكُمْ), (إِيَّاكُنَّ), (إِيَّاهُ), (إِيَّاهَا), (إِيَّاهُمَا), (إِيَّاهُمْ), and (إِيَّاهُنَّ).

The first of the Nouns in the state of Nasb is the Maf’ul bihi or the object.

It is divided again into implicit and explicit, just like the fa’il. The only difference is that the implicit forms of Maf’ul bihi are the only the ones mentioned:

مُتَّصِل: وضَرَبَنا، وضَرَبَكَ، وضَرَبَكِ، وضَرَبَكُما، وضَرَبَكُم، وضَرَبَكُنَّ، وضَرَبَهُ، وضَرَبَهَا، وضَرَبَهُمَا، وضَرَبَهُم، وضَرَبَهُنَّ.

مُنفَصِل: إيَّاي، وإيَّانا، وإيَّاكَ، وإيَّاكِ، وإيَّاكما، وإيَّاكم، وإيَّاكُنَّ، وإيَّاه، وإيَّاها، وإيَّاهما، وإيَّاهم، وإيَّاهُنَّ

بَابُ اَلمَصْدَرِ

The Absolute Object (المفعول المطلق)

اَلمَصْدَرُ هُوَ: اَلاِسْمُ المَنْصُوبُ اَلَّذِي يَجِيءُ ثَالِثًا فِي تَصْرِيفِ اَلفِعْلِ، نَحْوَ: ضَرَبَ يَضْرِبُ ضَرْبًا.

It’s the noun in the state of nasb that comes the third in the conjugation of the verb; for example: (ضَرَبَ يَضْرِبُ ضَرْبًا)

وَهُوَ قِسْمَانِ: لَفْظِيٌّ وَمَعْنَوِيٌّ، فَإِنْ وَافَقَ لَفْظُهُ لَفْظَ فِعْلِهِ فَهُوَ لَفْظِيٌّ، نَحْوَ: قَتَلْتُهُ قَتْلًا.

And it consists of two types: verbal and abstract. When the infinitive’s derivation agrees with the verb’s form, it’s a verbal infinitive. For example: (قَتَلْتُهُ قَتْلًا).

وَإِنْ وَافَقَ مَعْنَى فِعْلِهِ دُونَ لَفْظِهِ فَهُوَ مَعْنَوِيٌّ، نَحْوَ: جَلَسْتُ قُعُودًا، وَقُمْتُ وُقُوفًا، وَمَا أَشْبَهَ ذَلِكَ.

When the infinitive’s derivation is different from the verb’s form but they both have the same meaning, this is an abstract infinitive. For example: (جَلَسْتُ قُعُودًا) and (قُمْتُ وُقُوفًا) and the like.

المفعول المطلق or the absolute object is what is actually intended by this chapter. It is named Masdar because the المفعول المطلق is always in the form of Masdar – the original noun from which the verb is derived.

For example,

ضربَ يَضرِبُ ضَرْبَاً

ضَرْبَاً is the Masdar of ضربَ. To use it as المفعول المطلق you can say:

ضَرَبتُ السّارِقَ ضَرْباً مُبرِحاً

I beat the thief severely

If you translate this literally: I beat the thief with a severe beating.

The المفعول المطلق always comes after the verb, and it is Mansub Noun. It is sometimes used for emphasis and sometimes for describing the type or number of the verb.

There are numerous examples for المفعول المطلق in the Quran:

وَاللَّهُ أَنبَتَكُم مِّنَ الْأَرْضِ نَبَاتًا * ثُمَّ يُعِيدُكُمْ فِيهَا وَيُخْرِجُكُمْ إِخْرَاجًا

شُكْرًا is actually Maf’ul Mutlaq. It is short for:

أشكرُكَ شُكرا

In some cases, like the one above, the verb is hidden and the Maf’ul Mutlaq is mentioned directly.

The classification of the مصدر into literal and abstract is just a theoretical concept you need to keep in mind. The concept is clear from the text. If the verb and masdar come from the same word then it is literal. If it matches in meaning, but the words are different then, it is abstract.

بَابُ ظَرْفِ اَلزَّمَانِ وَظَرْفِ اَلمَكَانِ

Adverbials of Time and Place (المفعول فيه)

ظَرْفُ الزَّمَانِ هُوَ: اِسْمُ اَلزَّمَانِ اَلمَنْصُوبُ بِتَقْدِيرِ: (فِي) نَحْوَ: اَلْيَوْمَ، وَاللَّيْلَةَ، وغَدْوَةً، وَبُكْرَةً، وسَحَرًا، وَغَدًا، وعَتَمَةً، وَصَبَاحاً، وَمَسَاءً، وأبَدًا، وأمَدًا، وَحِينًا، وَمَا أَشْبَهَ ذَلِكَ.

The adverbial of time: it’s a Mansub noun that indicates or specifies time in a sentence. It acts as if there were a hidden (في = in or during) before it. For example: (اَلْيَوْمَ), (اللَّيْلَةَ), (غَدْوَةً), (بُكْرَةً), (سَحَرًا), (غَدًا), (عَتَمَةً), (صَبَاحاً), (مَسَاءً), (أبَدًا), (أمَدًا), (حِينًا), and anything like that.

وَظَرُفُ المَكَانِ هُوَ: اِسْمُ اَلمَكَانِ اَلمَنْصُوبُ بِتَقْدِيرِ: (فِي) نَحْوَ: أَمَامَ، وَخَلْفَ، وَقُدَّامَ، وَوَرَاءَ، وَفَوْقَ، وَتَحْتَ، وَعِنْدَ، وَمَعَ، وَإِزَاءَ، وَحِذَاءَ، وَتِلْقَاءَ، وَهُنَا، وَثَمَّ، وَمَا أَشْبَهَ ذَلِكَ.

The adverbial of place: it’s also a Mansub noun. It indicates or specifies space or location. It acts as if there were a hidden (في = in or at) before it. For example: (أَمَامَ), (خَلْفَ), (قُدَّامَ), (وَرَاءَ), (فَوْقَ), (تَحْتَ), (عِنْدَ), (مَعَ), (إِزَاءَ), (حِذَاءَ), (تِلْقَاءَ), (هُنَا), (ثَمَّ), and anything like that.

ظرفُ الزمان is the agent of time. It tells you when the the verb occurs.

وظرف المكان is the agent of place. It tells you where the action takes place.

These are formed by certains nouns that represent time and place, like the ones mentioned in the text.

But note that not all nouns that represent time and place are ظرف الزمان وظرف المكان. How do you tell them apart?

An important rule is that, when the Dharf Zaman or Makan is used in the sentence, it should be used in the context of (في). For example:

سَلَّمْتُ على محمدٍ صَباحًا

The meaning of the sentence is:

سَلَّمْتُ على محمدٍ في الصَّباحِ

But if you say:

أُحِبُّ الصباحَ

It is not used in the context of في and therefore not ظرف

The Zarf Zaman and Makan are always used in the context of (في) in Arabic.

Look at these two sentences:

المؤمنُ يخافُ يومَ القيامةِ

الكافر يخافُ يومَ القيامةِ

There is an important difference between the two sentences. In the first sentence يوم is مفعول به. In the second, it is ظرف زمان.

The first one means, the believer fears the Day of Judgement.

In the second sentence, the intended meaning is the disbeliever fears on the Day of Judgement.

الكافر يخافُ (فِي) يومِ القيامةِ

A general rule you can use to identify Zarf is:

For Zarf Zaman, the sentence should answer: When?

For Zarf Makan it should answer: Where?

If these answers can be found in the sentence, then it is Zarf.

More examples:

خَالِدِينَ فِيهَا أَبَداً

وَهُوَ الْقَاهِرُ فَوْقَ عِبَادِهِ

تَجْرِي تَحْتَهَا الأَنْهَارُ

Question: What about the ayah:

تَجْرِي مِن تَحْتِهَا الْأَنْهَارُ

Here it is not Zarf because of Min. Remember, the Zarf has to be Mansub always. If the Min is applied to it, it becomes جار ومجرور.

بَابُ الحَالِ

The Circumstantial Qualifier

اَلحَالُ هُوَ: اَلاِسْمُ اَلمَنْصُوبُ اَلمُفَسِّرُ لماَ اِنْبَهَمَ مِنْ اَلهَيْئَاتِ، نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: (جَاءَ زَيْدٌ رَاكِبًا) وَ(رَكِبْتُ الفَرَسَ مُسرَجًا) وَ(لَقِيتُ عَبْدَ اللهِ رَاكِبًا) وَمَا أَشْبَهَ ذَلِكَ.

The circumstantial qualifier: It’s a Mansub noun. It’s the noun that explains and clarifies any uncertain or unclear situation regarding the modality of the action. For example: (جَاءَ زَيْدٌ رَاكِبًا = Zayed came riding), (رَكِبْتُ الفَرَسَ مُسرَجًا = I rode a saddled horse), (لَقِيتُ عَبْدَ اللهِ رَاكِبًا = I met Abdullah who was riding), and so on.

وَلَا يَكُونُ اَلحَالُ إِلَّا نَكِرَةً، وَلَا يَكُونُ إِلَّا بَعْدَ تَمَامِ الكَلَامِ، وَلَا يَكُونُ صَاحِبُهَا إِلَّا مَعْرِفَةً.

The circumstantial qualifier is always and only indefinite (نَكِرَة). And it comes at the end of the sentence after the completed speech. And it only describes the conditions of a definite something or someone.

As you can see from the text, the purpose of the حال is to give more information regarding the action taking place.

Further, Ibn Ajrum says,

- The حال is always indefinite

- It always occurs at the end of the sentence.

- The subject of the sentence described by the حال is always definite.

What is the difference between حال and نعت ?

The نعت always follows the subject in being definite or indefinite.

The حال is always indefinite and its subject definite.

For example,

جاء الرجلُ الراكبُ (نعت)

The rider came.

جاء الرجلُ راكباً (حال)

The man came riding.

More examples:

دخلتُ المسجِدَ خافِياً

شرِبتُ اللّبَنَ ساخِنًا

بَابُ اَلتَّمْيِيز

The Specifying Element

اَلتَّمْيِيزُ هُوَ: اَلاِسْمُ المَنْصُوبُ، اَلمُفَسِّرُ لِماَ اِنْبَهَمَ مِنْ اَلذَّوَاتِ، نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: (تَصَبَّبَ زَيْدٌ عَرَقًا) وَ (تَفَقَّأَ بَكْرٌ شَحمًا) وَ (طَابَ مُحَمَّدٌ نَفْسًا) وَ (اِشْتَرَيْتُ عِشْرِينَ غُلَامًا) وَ (مَلَكْتُ تِسْعِينَ نَعْجَةً) وَ (زَيْدٌ أَكْرَمُ مِنْكَ أَبًا) وَ (أَجْمَلُ مِنْكَ وَجْهًا).

The specifying element: it’s a Mansub noun. It explains and clarifies anything that is unclear or uncertain regarding the quantity, quality, or the essence. For example:

(تَصَبَّبَ زَيْدٌ عَرَقًا) وَ (تَفَقَّأَ بَكْرٌ شَحمًا) وَ (طَابَ مُحَمَّدٌ نَفْسًا) وَ (اِشْتَرَيْتُ عِشْرِينَ غُلَامًا) وَ (مَلَكْتُ تِسْعِينَ نَعْجَةً) وَ (زَيْدٌ أَكْرَمُ مِنْكَ أَبًا) وَ (أَجْمَلُ مِنْكَ وَجْهًا).

وَلَا يَكُونُ إِلَّا نَكِرَةً، وَلَا يَكُونُ إِلَّا بَعْدَ تَمَامِ الكَلَامِ.

The specifying element is always indefinite, and it only comes at the end of the sentence.

The تمييز specifies and clarifies what is ambiguous about the action taking place or the noun it describes.

- The تمييز is always indefinite.

- It always comes at the end of the statement.

How to differentiate between حال and تمييز easily:

The حال always carries the meaning of (في) – in the state of.

For example, Zaid came (in the state of) riding.

Ahmed drank the milk (in the state of) standing up.

As for تمييز it comes with the meaning of (مِن) – of, in, in terms of.

I bought thirteen (of) apples.

I have more than you (in terms of) wealth and children.

More examples:

وَفَجَّرْنَا الْأَرْضَ عُيُونًا

مَلَكتُ تِسعِينَ نَعجَةً

أَنَا أَكْثَرُ مِنكَ مَالًا وَأَعَزُّ نَفَرًا

بَابُ اَلاِسْتِثْنَاءِ

Exception

وَحُرُوفُ اَلاِسْتِثْنَاءِ ثَمَانِيَةٌ: وَهِيَ إِلَّا، وَغَيْرُ، وَسِوًى، وَسُوًى، وَسَوَاءٌ، وَخَلَا، وَعَدَا، وَحَاشَا.

Translation: The particles of exception are eight. And they are:

(إِلَّا), (غَيْرُ) (سِوًى), (سُوًى), (سَوَاءٌ), (خَلَا), (عَدَا), and (حَاشَا).

فَالمُسْتَثْنَى بإِلاَّ يُنْصَبُ إِذَا كَانَ اَلْكَلَامُ تامًّا مُوجَبًا، نَحْوَ: (قَامَ القَوْمُ إِلَّا زَيْدًا) وَ (خَرَجَ اَلنَّاسُ إِلَّا عَمْرًا) وَإِنْ كَانَ اَلْكَلَامُ مَنْفِيًّا تَامًّا جَازَ فِيهِ اَلْبَدَلُ وَالنَّصْبُ عَلَى اَلاِسْتِثْنَاءِ، نَحْوَ: (مَا قَامَ اَلْقَوْمُ إِلَّا زَيْدٌ) وَ (إِلَّا زَيْدًا).

Translation: The word excepted by illa (إلا) gets nasb if the sentence was positive (affirmative) and complete. For example: (قَامَ القَوْمُ إِلَّا زَيْدًا), (خَرَجَ اَلنَّاسُ إِلَّا عَمْرًا). But if the complete sentence was negative (disaffirmed), the exception could be considered a Badl (apposition) of what it’s excepted from. Or it gets a nasb for being exception. For example: (مَا قَامَ اَلْقَوْمُ إِلَّا زَيْدٌ) and (إِلَّا زَيْدًا).

وَإِنْ كَانَ اَلْكَلَامُ نَاقِصًا كَانَ عَلَى حَسَبِ اَلْعَوَامِلِ، نَحْوَ: (مَا قَامَ إِلَّا زَيْدٌ) وَ (مَا ضَرَبْتُ إِلَّا زَيْدًا) وَ (مَا مَرَرْتُ إِلَّا بِزَيْدٍ).

And if the sentence is – when removing the exception – incomplete, the excepted thing’s grammatical classification depends on the factors of the sentence. For example: (مَا قَامَ إِلَّا زَيْدٌ), (مَا ضَرَبْتُ إِلَّا زَيْدًا), and (مَا مَرَرْتُ إِلَّا بِزَيْدٍ).

وَالمُسْتَثْنَى بِغَيْرٍ، وَسِوَى وَسُوَى، وَسَوَاءٍ مَجْرُورٌ لَا غَيْرُ.

And the exception by (غَيْرٍ), (سِوَى), (سُوَى), and (سَوَاءٍ) always gets Jarr state.

وَالمُسْتَثْنَى بِخَلا، وَعَدَا، وَحَاشَا يَجُوزُ نَصْبُهُ وَجَرُّهُ، نَحْوَ: (قَامَ القَوْمُ خَلَا زَيْدًا وَزَيْدٍ) وَ(عَدَا عَمْرًا وَعَمْرٍو) وَ(حَاشَا بَكْرًا وَبَكْرٍ).

And the word excepted by (خَلا), (عَدَا), and (حَاشَا) is allowed to get Nasb and Jarr. For example: (قَامَ القَوْمُ خَلَا زَيْدًا وَزَيْدٍ), (عَدَا عَمْرًا وَعَمْرٍو), and (حَاشَا بَكْرًا وَبَكْرٍ).

The Usage of إلا:

The particle إلا can be used in three situations:

| Example | State of the Noun after إلا | Type of sentence before إلا |

|---|---|---|

| ما رأيتُ إلا زيدًا | ||

| ما قامَ إلا زيدٌ | The same state it would have without إلا | Partial or incomplete sentence |

| ما قامَ القومُ إلا زيدٌ | ||

| ما قامَ القومُ إلا زيدًا | بدل أو نصب | Complete sentence with negation |

| قام القومُ إلا زيدًا | نصب | Complete sentence |

Now let’s look at this in more detail,

1.The إلا after the complete sentence:

This means that the part of the sentence before إلا is a complete sentence by itself, and would remain so if إلا and what comes after it is removed.

If you look at the sentence:

قام القومُ إلا زيدًا

The first part, قام القومُ is a complete and meaningful sentence by itself – the group (of people) stood up.

In this case, the noun after إلا has to be Mansub.

In order for a sentence with إلا to be considered complete, it has to have three elements:

The thing from with the exception is being made + agent of exception + the exception

In a complete exception, all three will be present.

If it is partial exception, then only agent of exception + exception will be present.

2.The إلا after a complete sentence with negation:

If the sentence is complete like in the first case, but with negation as in:

ما قامَ القومُ إلا

Then the noun after إلا can take two states:

a.You can treat it as an exception (الاستثناء) and give it Nasb:

ما قامَ القومُ إلا زيدًا

b.You can treat it as Badal, and here it takes the state of the element before إلا.

ما قامَ القومُ إلا زيدٌ

ما مررتُ بأحدٍ إلا زيدٍ

Therefore you find in one place in the Quran:

مَّا فَعَلُوهُ إِلَّا قَلِيلٌ مِّنْهُمْ

And in another:

فَشَرِبُوا مِنْهُ إِلَّا قَلِيلًا مِّنْهُمْ

In the first example, the noun after إلا is treated as ‘exception’ and in the second a badal.

Keep in mind:

The linguists say, if the things being exempted is not from the same kind as the the thing from which it is exempted, then it should always be Nasb. For example,

جاء القومُ إلا حِماراً

3.The إلا after a partial or incomplete sentence:

In this case, the إلا has no effect on the noun after it. The noun takes same the vowel ending it would have if it did not have إلا, based on its place in the sentence.

ما أكلتُ إلا خُبزًا

ما مررتُ إلا بزيدٍ

ما رَأَيتُ إلا زيدًا

Exceptions with

غيرُ، وسِوى، وسُوى، وسَوَاءٌ

As for these (غيرُ، وسِوى، وسُوى، وسَوَاءٌ) they are nouns and not particles. So when they are used as agents of exception, they will act as the مضاف and the noun after as مضاف إليه. The مضاف إليه is always Majrur/Makhfudh as we will learn in the next section: Makhfudhat Al Asma’

As for the agent of exception itself, it follows the same rules as إلا: Nasb if it is a complete sentence, Nasb or Badal if it is a complete sentence with negation, and Indifference to إلا if is an incomplete sentence.

قام القوم غيرَ زيدٍ

ما قام القوم غيرَ زيدٍ

Or

ما قام القوم غيرُ زيدٍ

ما قام غيرُ زيدٍ

Exceptions with

خَلا ، وعَدَا، وحاشا

These three: خَلا ، وعَدَا، وحاشا can be treated as both particles and verbs at the same time. Based on that, the coming after can be given either Nasb or Khafdh (Jarr) in all cases (without negation).

قام القوم خلا زيدًا

قام القوم خلا زيدٍ

If ما of negation is added the agent to make it: (ما خَلا ، ما عَدَا، ما حاشا) then it has to be Nasb always.

قام القوم ما خلا زيدًا

بَابُ لَا

Absolute Negation

اِعْلَمْ أَنَّ (لَا) تَنْصِبُ اَلنَّكِرَاتِ بِغَيْرِ تَنْوِينٍ إِذَا بَاشَرَتْ اَلنَّكِرَةَ وَلَمْ تَتَكَرَّرْ (لاَ) نَحْوَ (لَا رَجُلَ فِي اَلدَّارِ).

Know that Laa (لا) gives Nasb to the indefinite word that doesn’t have Tanween when the word is directly preceded by (لا) and when (لا) isn’t repeated. For example: (لَا رَجُلَ فِي اَلدَّارِ).

فَإِنْ لَمْ تُبَاشِرْهَا وَجَبَ اَلرَّفْعُ وَوَجَبَ تَكْرَارُ (لَا) نَحْوَ (لَا فِي اَلدَّارِ رَجُلٌ وَلَا اِمْرَأَةٌ).

If the word isn’t directly preceded by (لا), Raf’ (رفع) case is mandatory for the indefinite word. And (لا) must be repeated if another word is negated. For example: (لَا فِي اَلدَّارِ رَجُلٌ وَلَا اِمْرَأَةٌ).

فَإِنْ تَكَرَّرَتْ (لَا) جَازَ إِعْمَالُهَا وَإِلْغَاؤُهَا، فَإِنْ شِئْتَ قُلْتَ: (لَا رَجُلٌ فِي اَلدَّارِ وَلَا اِمْرَأَةٌ).

When Laa (لا) is repeated. It’s allowed to either activate its effect or neglect it. One can say: (لَا رَجُلٌ فِي اَلدَّارِ وَلَا اِمْرَأَةٌ).

We already learned about the action of لا upon verbs. It is one of the particles of Jazm. Here we are going talk about لا with respect to nouns.

Please note that here we will be using لا with indefinite nouns. And the purpose of this لا is absolute negation. For example:

لا رجلَ في الدار

Which mean there is no man in the house. Not even a single one.

This is what we mean by absolute negation as opposed to specific negation. The noun which is negated in this case is Mansub.

If the noun is definite, then it will be Marfu’ instead, and the negation will be specific, as we are negating a specific thing. For example:

لا الرجُلُ في الدار

The man is not in the house.

There are three ways the لا can be used with respect to indefinite nouns:

- It comes directly before the noun and is not repeated. In this case, it acts exactly like إنّ, except for the tanween. This means that the لا causes the subject to take Nasb and the predicate to take the state of Raf’ or Dhamma. However, it does not give the tanween.

This is the case in the example we saw before,لا رجلَ في الدار - It does not come directly before the noun. In this case, the noun is given the state of Raf’ and the لا is repeated. For example,لا في الدار رجلٌ ولا امرأةٌ

- It comes directly before the noun and is repeated. In this case, both the above states can be given to it (Nasb without tanween and Raf’ with tanween):لا رجلَ في الدار ولا امرأةَلا رجلٌ في الدار ولا امرأةٌ

One of the most common usages of the لا of absolute negation is in the expression:

لاَ إلهَ إلاَّ اللهُ

There is no deity (worthy of worship) other than Allah

بَابُ المُنَادَى

Vocative (Agent for Calling)

اَلمُنَادَى خَمْسَةُ أَنْوَاعٍ: المُفْرَدُ اَلعَلَمُ، وَالنَّكِرةُ اَلمَقْصُودَةُ، وَالنَّكِرةُ غَيْرُ اَلمَقْصُودَةِ، وَالمُضَافُ، وَالشَّبِيهُ بِالمُضَافِ.

The vocative is five types: the single proper name, the intended indefinite noun, the unintended indefinite noun, the adjunct noun, that which is similar to the adjunct nouns.

فَأَمَّا اَلمُفْرَدُ اَلْعَلَمُ وَالنَّكِرةُ اَلمَقْصُودَةُ فَيُبْنَيَانِ عَلَى اَلضَّمِّ مِنْ غَيْرِ تَنْوِينٍ، نَحْوَ: (يَا زَيْدُ) وَ(يَا رَجُلُ). وَالثَّلَاثَةُ اَلْبَاقِيَةُ مَنْصُوبَةٌ لَا غَيْرُ.

For the single proper name and the intended indefinite, they both are formed or written with Damma without Tanween. For example: (يَا زَيْدُ) and (يَا رَجُلُ). And the rest three types always get Nasb state.

The principles of the call in Arabic are as follows:

1.If the what comes after the particle of calling (يا) is singular, and the intended target is specific, then the noun after it take dhamma (or what comes in its place). For example:

يا محمدُ، يا مريمُ، يا مسلمونَ

2.If the noun is made up of two words, then the first word will always take fatha (or what comes in its place):

يا معلِّمَ المَدْرَسَةِ

يا حافظَ القرآنِ

يا أصحابَ القريَةِ

Ibn Ajrum mentions things that which resemble compound nouns as well. What is intended by this are situations were two words are linked together, but not as Mudaf and Mudaf Ilaihi. For example:

يا رحيماً بالعبادِ

يا جميلاً خَطُّهُ

يا حافِظاً القرآنَ

As you can see these words are treated with the same rules.

3.If the target of the call is general and not specific, then it is given Nasb. For example,

يا طالبًا اجْتهِد

O’ Student, work hard.

Here you are not calling upon a particular student, but all students in general.

But what if you wanted to address only a specific student in front of you? Then you say:

يا طالبُ اجْتَهِد

More examples:

يَا جِبَالُ أَوِّبِي مَعَهُ

يَا دَاوُودُ إِنَّا جَعَلْنَاكَ خَلِيفَةً فِي الْأَرْضِ

يَا صَاحِبَيِ السِّجْنِ أَأَرْبَابٌ مُتَفَرِّقُونَ خَيْرٌ أَمِ اللَّهُ الْوَاحِدُ الْقَهَّارُ

بَابُ اَلمَفْعُولِ مِنْ أَجْلِهِ

The Causative Object

وَهُوَ اَلاِسْمُ المَنْصُوبُ، اَلَّذِي يُذْكَرُ بَيَانًا لِسَبَبِ وُقُوعِ اَلفِعْلِ، نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: ( قَامَ زَيْدٌ إِجْلَالًا لِعَمْرٍو) وَ (قَصَدْتُكَ اِبْتِغَاءَ مَعْرُوفِكَ).

It’s a Mansub noun. It gets mentioned to explain and clarify the reason why a verb action has occurred. Such as: (قَامَ زَيْدٌ إِجْلَالًا لِعَمْرٍو) and (قَصَدْتُكَ اِبْتِغَاءَ مَعْرُوفِكَ).

As explained in the text, the المفعول لأجله is a noun in the state of Nasb which explains the reason for the action that takes place. It is also known as المفعول له.

You can see this in the examples given in the text. Also, it always takes the form of Masdar.

المفعول لأجله always answers the question: Why?

More examples:

وَالَّذِينَ يُنفِقُونَ أَمْوَالَهُمْ رِئَاءَ النَّاسِ

وَالَّذِينَ صَبَرُوا ابْتِغَاءَ وَجْهِ رَبِّهِمْ

وَلَا تُمْسِكُوهُنَّ ضِرَارًا

قدِمَ المسلمونَ للمدينةِ زيارةً للمسجدِ

بَابُ اَلمَفْعُولِ مَعَهُ

The Accompanying Object

وَهُوَ اَلاِسْمُ اَلمَنْصُوبُ، اَلَّذِي يُذْكَرُ لِبَيَانِ مَنْ فُعِلَ مَعَهُ اَلفِعْلُ، نَحْوَ قَوْلِكَ: (جَاءَ اَلْأَمِيرُ وَالْجَيْشَ) و(اِسْتَوَى اَلمَاءُ وَالْخَشَبَةَ).

It’s a Mansub noun. It gets mentioned to explain or clarify the one who has shared the action with the subject. For example: (جَاءَ اَلْأَمِيرُ وَالْجَيْشَ) and (اِسْتَوَى اَلمَاءُ وَالْخَشَبَةَ).

وَأما خَبَرُ (كَانَ) وَأَخَوَاتِهَا، وَاسْمُ (إِنَّ) وَأَخَوَاتِهَا، فَقَدْ تَقَدَّمَ ذِكْرُهُمَا فِي اَلمَرْفُوعَاتِ، وَكَذَلِكَ اَلتَّوَابِعُ، فَقَدْ تَقَدَّمَتْ هُنَاكَ.

As for the predicate of Kana (كان) and its sisters, and the noun of Inn (إن) and its sisters, they were already mentioned and explained in the chapter of Nouns that get Raf (رفع) state. Same for the nouns that follow Mansub nouns (followers).

It is a way of mentioning something along with the action. The و here is known as واو المعية or the و of accompaniment. In this case, this additional object is given the state of Nasb.

The و in the مفعول معه takes the meaning of مع or ‘with’

Examples:

فأجمِعُوا أمرَكم وشُرَكاءَكم

وشُرَكاءَكم is treated as Maf’ul Ma’ahu here because it cannot be ‘Atf on أمرَكم. (Due to the meaning)

والذين تَبَوَّؤُا الدارَ والإيمانَ

والإيمانَ is treated as Maf’ul Ma’ahu here because it cannot be ‘Atf on الدارَ

سافرَ خليلٌ والليلَ

Khalil travelled with the night.

ما لكَ وسعيداً؟

What is your problem with Sa’eed?

بَابُ اَلمَخْفُوضَاتِ مِنْ اَلأَسْمَاءِ

The Nouns in the state of Khafdh

اَلمَخْفُوضَاتُ ثَلَاثَةُ أَنْوَاعٍ: مَخْفُوضٌ بِالْحَرْفِ، وَمَخْفُوضٌ بِالْإِضَافَةِ، وَتَابِعٌ لِلْمَخْفُوضِ.

Nouns in the state of Khafd are three types: Noun that gets Khafd state because of a proposition, noun that gets Khafd state because of adjunct, and a noun that follows the noun in the state of Khafd.

فَأَمَّا المَخْفُوضُ بِالحَرْفِ فَهُوَ مَا يُخْفَضُ بِمِنْ، وَإِلَى، وَعَنْ، وَعَلَى، وَفِي، وَرُبَّ، وَالْبَاءِ، وَالْكَافِ، وَاللاَّمِ، وَبِحُرُوفِ اَلْقَسَمِ، وَهِيَ: اَلْوَاوُ، وَاَلْبَاءُ، وَالتَّاءُ، وَبِوَاوِ رُبَّ، وَبِمُذْ، وَمُنْذُ.

As for the nouns that get Khafd because of a proposition, they are the nouns that follow the following particles: (مِنْ), (إِلَى), (عَنْ), (عَلَى), (فِي), (رُبَّ), (الْبَاءِ), (الْكَافِ), (اللاَّمِ،), and the particles of Oath: (اَلْوَاوُ), (اَلْبَاءُ), (التَّاءُ), (بِوَاوِ رُبَّ), (بِمُذْ), and (مُنْذُُ).

وَأَمَّا مَا يُخْفَضُ بِالْإِضَافَةِ، فَنَحْوُ قَوْلِكَ: (غُلَامُ زَيْدٍ) وَهُوَ عَلَى قِسْمَيْنِ مَا يُقَدَّرُ بِاللاَّمِ، وَمَا يُقَدَّرُ بِمِنْ، فَاَلَّذِي يُقَدَّرُ بِاللاَّمِ، نَحْوُ: (غُلَامُ زَيْدٍ) وَاَلَّذِي يُقَدَّرُ بِمِنْ، نَحْوُ: (ثَوْبُ خَزٍّ) وَ(بَابُ سَاجٍ) وَ(خَاتَمُ حَدِيدٍ).

As for the nouns that get Khafd because of an adjunct such as (غُلَامُ زَيْدٍ). And this type consists of two groups, the one which implies the particle Lam (لام) such as: (غُلَامُ زَيْدٍ). And the one which implies the particle Min (من) such as: (ثَوْبُ خَزٍّ), (بَابُ سَاجٍ), and (خَاتَمُ حَدِيدٍ).

تَمَّ بحَمْدِ الله.

Completed with all thanks and praise to Al-Mighty Allah.

The Makhfudhat are very straightforward and the concise explanation in the text is sufficient.

The تابع للمخفوض are:

- Na’at

- ‘Atf

- Tawkeed

- Badal

All of which we have learned under Marfu’at. If these follow an element that is in the state of Khafdh then they take Khafdh as well.

For example,

مررتُ بزيدٍ وعَمرٍو

بَلْ مَكْرُ اللَّيْلِ وَالنَّهَارِ

More examples:

أخذتُ الكتابَ من زيدٍ

ما رأَيتُهُ مُذْ أمسٍ

رَأَيتُ غُلامَ زيدٍ

الْحَمْدُ لِلَّهِ رَبِّ الْعَالَمِينَ

And with that, we have reached the end of the Ajrumiyyah. These are the core concepts of I’rab. With a deep understanding of all the text, reading the Matn multiple times and even memorising it. can be very beneficial for the beginner.

You will find yourself going back to these core concepts for the remainder of your Arabic journey.

All praise and blessings are due to Allah the Almighty,

May peace and blessings be upon the Prophet.

References:

Sharh:

شرح متن الآجرومية في النحو – الشيخ د. سليمان بن عبد العزيز العيوني

شرح الآجرومية للشيخ محمد بن صالح بن العثيمين

Translations:

Previous Lesson:

Arabic Grammar For Beginners Based On Al-Ājrūmīyyah (Part 4: Verbs)

Lesson One:

Arabic Grammar For Beginners Based On Al-Ājrūmīyyah (Part 1: Al-Kalam)